FUN, FUN, FUN!

https://sportliterate.org/wp-content/themes/osmosis/images/empty/thumbnail.jpg 150 150 bjj-sportliterate bjj-sportliterate https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/592f60292ffae558017e7047d039bebe88be7eca3a999965f3a7f0501ad82d49?s=96&d=mm&r=gFUN, FUN, FUN!

A Review of Taro Gomi’s Run, Run, Run!

by Scott F. Parker

Taro Gomi was already a household favorite in my family, thanks to his classic Everyone Poops, which we have long quoted and laughed at and learned from. The art in Gomi’s latest book to be translated into English from the original Japanese, Run, Run, Run!, a board book, is reminiscent of his best-known work. Plain-colored backgrounds, in this case white, featuring simple figures in action, in this case mostly running, don’t just illustrate the story but play a crucial role in its telling.

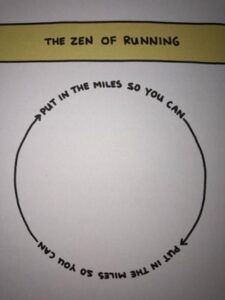

The narrative announces itself from the start: “It’s time to race!” Five children approach the start line and await the starter’s signal. From the moment the gun fires, it’s only a page until the first child crosses the finish line, where she receives a flag numbered 1. But wait, the text tells us, “Running is fun!” Are we really at the finish line already? The book just started. As the second, third, and fourth runners accept their numbered flags, the last runner continues past the finish line. The next several pages see this runner take to city streets, neighborhoods, fields, and forests. If running is fun, Run, Run, Run! asks, why would anyone stop?

Eventually, though, if you run far enough you come back to where you began, as the child in the book does, approaching the finish line a second time. This time, however, a dog that has been following the child since the farm surges into the lead and claims fifth place in the race, bumping our hero back to sixth. This is how far behind our hero has fallen: finishing sixth in a five-kid race.

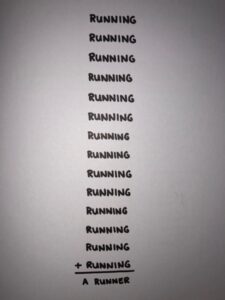

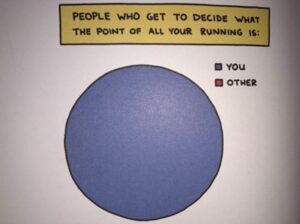

Meaningless childish silliness? I don’t think so. Or, rather, not just. Gomi’s runner is not merely eccentric. The child understands what the race is and what it’s for but chooses, despite this, to break out of the race’s constraints entirely. The reader’s expectations about the narrative are revealed as this child asserts the right to make new rules. Why can’t a race be run without racing? Why can’t a book start one story only to tell another? Run, Run, Run! is as liberatory to the adult reader as it is perfectly sensible to the child reader.

What could be more sensible, more logical, than to explore the world by foot, to proceed according to what’s fun, to run your own kind of race, to be your own kind of self? Does it sound childish. Great wisdom usually does.

Scott F. Parker is the author of Run for Your Life: A Manifesto and The Joy of Running qua Running, among other books. His writing has appeared in Runner’s World, Running Times, Tin House, Philosophy Now, the Believer, and other publications. He teaches at Montana State University and is the nonfiction editor for Kelson Books.