Running with Greeks

https://sportliterate.org/wp-content/themes/osmosis/images/empty/thumbnail.jpg 150 150 bjj-sportliterate bjj-sportliterate https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/1b3ceda989693317c6e5b76996b682ca?s=96&d=mm&r=gRunning with Greeks

A Review of Sabrina Little’s The Examined Run: Why Good People Make Better Runners

& Andrea Marcolongo’s The Art of Running: Learning to Run Like a Greek

by Scott F. Parker

As runners, Andrea Marcolongo and Sabrina Little have almost nothing in common. Little is an elite

runner, with five U.S. national championships and a silver medal in the World 24-Hour Championships to her credit. Marcolongo, by contrast, was bookishly inactive life prior to, somewhat quixotically, taking up running in her thirties. But as students of running, both writers recognize the happy congruence between their sport and the culture of ancient Greece that is their first common passion.

That their two books should arrive in the same publishing season (Marcolongo’s in translation from the Italian) suggests to this hopeful reviewer the possibility of a shifting societal attitude away from the treatment of running as one more of life’s endeavors to be efficiencied and technologized into optimal performance (At one point in her book, Marcolongo wonders whether coaches think they’re working with athletes or machines.) and toward an activity that can be seen foremost as an expression of human nature.

Many authors before Little and Marcolongo have gone to literal and historical Greece in their writing about running. What sets these new books apart is that they are not satisfied with summarizing the legend of Philippides’s ultimate run from Marathon to Athens; instead, each in her own way engages seriously with the philosophy and literature of ancient Greece. Why? Simply, it turns out — and maybe we shouldn’t be surprised — because the Greeks have something to teach us.

Little, a philosopher by profession, noticed the convergence between the virtue ethics she studied and the virtues that running promoted in her life, and from there began a systematic inquiry into the relationship between running and moral virtue that resulted in The Examined Run.

From the outset, Little makes it clear that running is a human enterprise that happens in the context of a human life, a point she makes succinctly later in the book: “We are not just runners. We are humans.” This simple-seeming point is crucial for Little’s project, which “attempts to restore to sport a vision of the good life and how running fits in.” Equally important for Little is the recognition that humans are embodied beings. What counts is accepting our physical constraints and working with them, not transcending them through some disembodied act of will. As she writes, “we can create something beautiful within the limits we have. This would demand that we think about sports and life in richer, broader ways than the rhetoric of limitlessness affords us.”

According to Little’s assessment, running, like sports in general, tends to be too narrowly concerned with results that it assumes are distinct from an athlete’s broader well-being. But any athlete who pays sufficient attention to the experience of athletics will observe the many ways in which their sport is enmeshed with the rest of their lives and the tensions can arise between success and well-being. An unbalanced devotion to one’s sport, to pick the easiest example, comes at the cost of trade-offs to one’s other interests, be they social, familial, intellectual, or whatever other dimensions of human life contribute to the good life. Relatedly, the culture of running that concentrates its attention only on performance reduces the person who runs to its limited conception of a runner. It can be as dehumanizing as an employer seeing employees as abstract sources of labor. But in response to any book or podcast or coach that addresses only the abstract running body we can say that there are more things in being human than are dreamt in any training schedule. Little, never one to objectify, theorizes from experience when she writes of running’s effects, “But it was not just my body that changed. My character was edified, too.”

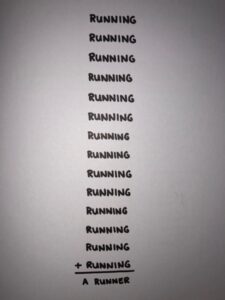

Recognizing Little’s claim about the effects of running extending beyond the physical, important questions follow about what constitutes character, virtue, and the good life. Little’s Aristotelianism holds that “virtues are excellences suited to the kind of being we are, and, in the classical tradition, they are constitutive goods of our nature. They are a means of becoming higher versions of ourselves, rather than turning us into something else.” That is to say that through the exercise of virtue we can become better versions of ourselves, even one of Aristotle’s virtuous persons, who “has a correct conception of the good, is motivated to perform these good actions, and does indeed perform them.” Virtue, by this understanding, is the stuff of theory in action. For Little, as for Aristotle, “both moral and intellectual virtues are acquired rather than natural.” And they are acquired through practice: “We develop good characters in the same way that we become better runners.”

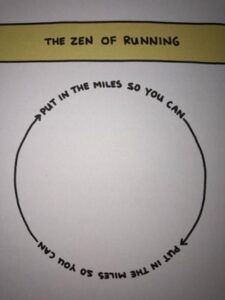

This takes us to the core of Little’s argument and her original contribution to the discourse of virtue ethics: the recognition that running — not uniquely, but unmistakably — leads to a virtuous circle by which it cultivates better character, which cultivates better running. For example, Little argues, running promotes the virtues of resilience, joy, perseverance, and humor, which then become performance-enhancing virtues for the runner.

We could apply Little’s framework in the case of someone like the elite runner Kara Goucher, whose testimony against Alberto Salazar revealed a multitude of coaching violations. It’s possible that Goucher developed her patience (she had to wait years for her testimony to lead to sanctions against Salazar) and courage (to speak out when a successful outcome was not guaranteed but the enormous emotional cost on her was) at least in part through running, those being two of the virtues Little returns to in her analysis. Multiple studies have found that professional ethicists are no more ethical than the average person. From an Aristotelian vantage, it’s easy to observe that knowing a lot about the subject of ethics is far removed from developing one’s virtues through deliberate practice. If Little has the research funds available to her, it might be worthwhile to conduct a similar study of runners. Does the evidence support her first-hand experience and philosophical reflection? Are there a higher percentage of Gouchers among us than the general population? I, for one, would be curious to know.

In the same spirit of recommending a life that balances body and mind, Little once again follows the path of the ancients: “This is why Plato, Aristotle, and the classical tradition that succeeds them include poetry as a humanizing complement to gymnastics — because gymnastics alone would form young citizens of brutes.” The approach one takes to running determines the degree to which it will positively shape one’s character. The mind must be engaged as well as the body, and along certain specific lines that The Examined Run both identifies and attempts to engage. The opposite is true as well. Reading this book without then going for a run would be like reading recipes online and never stepping foot in the kitchen. People do it. But we don’t call it thriving.

While Little’s loadstar is Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Andrea Marcolongo’s is Philostratus’s Gymnasticus. Philostratus — “The Athenian” — was a Greek writer in the Roman era, whose treatise includes accounts of early Olympic games. But it’s as “the first sports manual” that Marcolongo reads Gymnasticus. And she is delighted by what she finds in it: “He wasn’t trying to tell us how to play sports, or in what sequence to exercise our mortal muscles, or why we should exercise, compiling a list of practical benefits. At its core his book seeks to understand what sports are — and therefore what we talk about when we talk about physical activity.” The echo of Murakami is intentional, as the echo of Philostratus will be, too, in The Art of Running, which takes the very approach Marcolongo identifies in the Athenian.

Gymnasticus. Philostratus — “The Athenian” — was a Greek writer in the Roman era, whose treatise includes accounts of early Olympic games. But it’s as “the first sports manual” that Marcolongo reads Gymnasticus. And she is delighted by what she finds in it: “He wasn’t trying to tell us how to play sports, or in what sequence to exercise our mortal muscles, or why we should exercise, compiling a list of practical benefits. At its core his book seeks to understand what sports are — and therefore what we talk about when we talk about physical activity.” The echo of Murakami is intentional, as the echo of Philostratus will be, too, in The Art of Running, which takes the very approach Marcolongo identifies in the Athenian.

That Marcolongo would take her lead from such an obscure source is explained by her first love and the subject of her first book: the Greek language. Marcolongo is a journalist by trade, and what she lacks in knowledge about running she makes up for in curiosity and essayistic spirit. Planted unapologetically in the center of her own very particular perspective, Marcolongo sees running through a beginner’s eyes, without the assumptions and blind spots of someone who has grown up in the sport.

It is this love of the Greek language and Greek history that, when she takes up running during the pandemic, prompts Marcolongo to register for the Athens Marathon, which serves as a framing device for the book and, one gathers, an effort made significantly for the sake of the book that would result. She will train to retrace the famous route of Philippides’s from Marathon, and along the way she will respond from myriad sides to the question of why we (herself now included) run.

Since Marcolongo doesn’t bury the lede, I see no need to. She comes quickly to the realization that “When I run, I’m not getting on with my life; I’m living.” Running for her is an end in itself. She could stop the book right there. What else is there to say, really? Well, how about unpacking the nature of the end in itself: “Every time I go for a run, long or short, my body and, by some miracle, my head along with it — that’s what runners mean when they talk about ‘mental health’ — does everything in its power to reach its one goal: to live life to the fullest, or at least far more than my body is permitted to when it’s planted in a chair. . . . This completeness of motion, pace Philostratus, is a love of life. Nothing more, nothing less — and therefore everything.”

As if that were not enough already to get us all out of our seats, let me offer one more glimpse into what it’s like to see running as Marcolongo does: “Running is the most contemplative activity there is. Once upon a time people considered it a mystical form of pilgrimage. Finally at a remove — freed — from the thousands of daily distractions, we’re left to contemplate only two landscapes when we run: the interior landscape of emotions and physical sensations, and the exterior landscape of streets, trees, rivers, and, for those lucky enough, mountains and seas.” The fact that the author of this fine sentiment could be someone who runs with earbuds, as Marcolongo reports doing, beggars my belief. But much of the charm of The Art of Running is Marcolongo’s idiosyncrasy. Her wandering mind sometimes wanders into some strange claims, such as “I’ve never heard a runner sing the praises of running while running.” But even when I don’t agree with her, it’s so refreshing to read someone thinking original pretenseless things about running.

Marcolongo’s beginner eyes also let her see things many runners take for granted. For instance, the fact that we take off most of our clothes and then run in public spaces, where we are sure to be seen by countless others. That’s unusual. “‘I’m going for a run,’ a phrase every runner uses, means crossing the threshold of polite society, which as a matter of decorum bars us from attending to our bodily needs in public, and visibly invading spaces where physical exercise is, as a rule, alien.” Most running books, needless to say, fail to address such fundamental dimensions of the sport, something Marcolongo does as routinely as she laces up her shoes. Then again, most running books fail to recognize that “we all need a little poetry in our lives, especially when we’re running.”

That is the enduring lesson of these two books—that the inner life of the runner is not separate from the outer, the two are entwined in the nature of the human. Understood broadly — and how would we want to understand but broadly? — running is about what it means to be a human being. The Examined Run and The Art of Running make this plain and, what’s more, offer to assist in attuning our mental and physical, not to mention our spiritual, faculties.

Happy trails, everyone.

Scott F. Parker is the author of Run for Your Life: A Manifesto and The Joy of Running qua Running, among other books. His writing has appeared in Runner’s World, Running Times, Tin House, Philosophy Now, the Believer, and other publications. He teaches at Montana State University and is the nonfiction editor for Kelson Books.