Just Running

https://sportliterate.org/wp-content/themes/osmosis/images/empty/thumbnail.jpg 150 150 bjj-sportliterate bjj-sportliterate https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/1b3ceda989693317c6e5b76996b682ca?s=96&d=mm&r=gJust Running

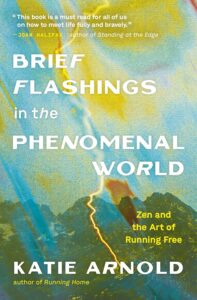

A Review of Katie Arnold’s Brief Flashings in the Phenomenal World

by Scott F. Parker

In Jon J. Muth’s picture book Zen Shorts, a panda named Stillwater tells traditional Zen stories to a set of three siblings. Among these is the story of the Chinese farmer, whose luck seems to fluctuate wildly over the course of a series of related events. First, he loses a horse. Then, the horse returns, trailed by wild horses that become his. Next, the farmer’s son breaks his leg riding one of the wild horses. Finally, the army comes through and conscripts every able-bodied young male, a category to which the farmer’s son no longer belongs. With the equanimity of a sage, and to the befuddlement of his community, the farmer keeps an even keel through these (seeming) ups and downs. Whether a given event is an instance of good or bad luck is never known. “We’ll see,” he says about each. As the youngest sibling in Muth’s book helpfully interprets for the reader: “Good and bad are all mixed up.”

Katie Arnold read Zen Shorts to her two daughters when they were young, a fact she recalls after her own leg is broken in a terrifying rafting accident. But Arnold is more skeptical than the farmer. It’s one thing to take a moral lesson from a parable. It’s another thing entirely to have the grace and practical wisdom to live by that moral. Admitting her skepticism, Arnold writes, “I had trouble getting on board with this idea at first. It seemed bogus, frankly. Of course there is good and bad in the world; terrible things happen to people, catastrophic things, atrocities, and there isn’t always a silver lining.”

Katie Arnold read Zen Shorts to her two daughters when they were young, a fact she recalls after her own leg is broken in a terrifying rafting accident. But Arnold is more skeptical than the farmer. It’s one thing to take a moral lesson from a parable. It’s another thing entirely to have the grace and practical wisdom to live by that moral. Admitting her skepticism, Arnold writes, “I had trouble getting on board with this idea at first. It seemed bogus, frankly. Of course there is good and bad in the world; terrible things happen to people, catastrophic things, atrocities, and there isn’t always a silver lining.”

How un-Zen of Arnold. But with the help of her friend Natalie Goldberg she’s coming around. She thinks of Muth’s book after Goldberg reminds her of the central Zen tennent that there is “No good, no bad—just this.” This wisdom, that it is not the world itself that is the source of our suffering but our judgments about the world, is one that Arnold has approached previously through running. The challenge for her is to carry that wisdom from running to her life broadly, a life that suddenly now does not include running. “I see that I don’t have to banish thoughts or make them cheerful. I just have to acknowledge them, note the fuss inside my head the same way I met the mountain when I ran up it, some days with a thrilling effortlessness, other days with unwanted difficulty. Running has taught me how to accept both. I used to run up a mountain; now I can sit like one.”

Accessing the spirit of the mountain, Arnold sees that the parable doesn’t have to be read skeptically but can be inhabited. “That my broken leg might be a form of liberation seems wildly paradoxical, in its own way mind-twistingly awesome. I want it to be true, but it is still too soon to tell.”

Everything I’ve quoted so far comes from one page midway through Brief Flashings in the Phenomenal World: Zen and the Art of Running Free, Arnold’s second book. Her first was the much-praised memoir Running Home, a meditation on grief and mortality, following her father’s death. Running Home factors crucially in Arnold’s new book. She is writing the first book as she rests and rehabs her leg in the narrative the second. One of the unforeseen consequences of her leg injury is the time and stillness it affords her to write. But Arnold’s takeaway isn’t a simple acceptance that there is a silver-lining to her injurty after all. She is a much subtler observer of her own experience than that.

Arnold’s injury thrusts her into uncertainty not just about her fortunes but about her self. Running for her had not been a hobby, but not just because she was good at it (elite-ultra-runner good). Running was Arnold’s way of being in the world. After her accident, there is a real chance she might not run again and therefore a real sense in which she might not be herself anymore. Naturally, this situation propels her self-reflection. Who is she if she isn’t running? Who is she if she isn’t a runner? Her response to such questions has the power to annihilate: “At its best, running is a true expression of the deepest part of me, but at its worst, it’s a crutch that feeds my ego; how attached I’ve grown to the word runner.”

And so, what has been Arnold’s practice becomes the object of her new (Zen) practice. The Venn diagram of runners and Zen practitioners isn’t a circle, but the overlap between the two groups is substantial. The kind of person who finds meaning in one is uncommonly likely to find it in the other. Reading Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind during her rehab, Arnold makes the natural comparison: “I realized that if I replaced ‘sitting’ with running, he and I were speaking the same language. After all, the main principles of Zen—form, repetition, stamina, impermanence, suffering, awakening—aren’t so different from those of long-distance running, or anything you do with great purpose.”

Sitting instead of running gives Arnold the chance to be what Suzuki would hope for her: “my broken leg had broken the cycle. Like it or not, I was a beginner again.” And learn to like it she does, demonstrating that the only path for us is the one we’re on. The awakening Arnold relates in Brief Flashings is honest; and the authenticity with which she relates it, affecting. This isn’t a treatise or a commentary but a sincere expression of what it’s like to be human in a changing world. Arnold is an adept memoirist, drawing meaning and wisdom from experience without a trace of self-indulgence.

At the end of the book, her rehab complete, Arnold returns to competitive ultrarunning. As impressive as that feat is (not to mention that she wins the sport’s most iconic race), what is truly inspiring about Arnold’s writing is how she is able to find what she is looking for in running and then find it again in not running. If she can do that, I want to say, anything is possible. This is a profound work of embodied spirituality.

Scott F. Parker is the author of Run for Your Life: A Manifesto and The Joy of Running qua Running, among other books. His writing has appeared in Runner’s World, Running Times, Tin House, Philosophy Now, The Believer, and other publications. He teaches at Montana State University and is the nonfiction editor for Kelson Books.